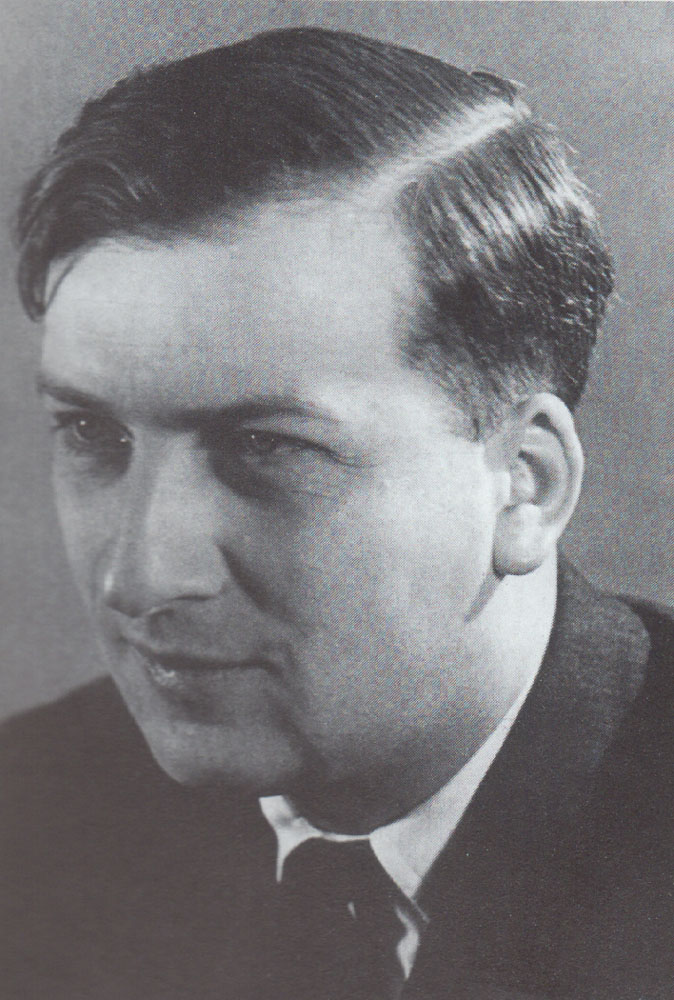

Pascal Copeau

Légende :

Pascal Copeau, représentant du mouvement Libération-Sud au Conseil National de la Résistance

Pascal Copeau, a journalist who was fiercely anti-Nazi, joined Libération-Sud in 1942. In the summer of 1943, he took over for Emmanuel d'Astier as head of Libération-Sud, which he represented within the MUR, and later on within the CNR. His role was essential in the Resistance.

Genre : Image

Type : Portrait

Source : © Archives privées Raymond Aubrac Droits réservés

Détails techniques :

Photographie analogique en noir et blanc.

Lieu : France

Contexte historique

![]()

Pascal Copeau naît à Paris le 23 octobre 1908 à Paris. Il est le fils de l'homme de théâtre Jacques Copeau, qui fonde la Nouvelle revue française aux côtés d'André Gide et de Jean Schlumberger, en 1908. Dès son enfance, il cotoie artistes et intellectuels tels Charles Dullin, Louis Jouvet, Gaston Gallimard ou encore Roger Martin du Gard.

Elève brillant, il entreprend des études d'histoire, de droit, et fréquente l'Ecole libre des sciences politiques. Parlant danois, anglais et allemand, il devient journaliste et séjourne à Berlin d'avril 1933 à novembre 1936 comme correspondant du Petit Journal. A son retour à Paris, en 1937, cet antinazi convaincu devient rédacteur en chef de Lu, puis de Vu et Lu, où il a sous ses ordres un journaliste du nom de... Emmanuel d'Astier de la Vigerie.

En juillet 1938, grâce à Pierre Brossolette, il est nommé responsable des émissions en langue allemande de Radio-Strasbourg, avant de se voir confier, en février 1939, l’ensemble des émissions en langues étrangères de la Radiodiffusion française.

Brièvement mobilisé en août, rappelé à la radio, il a à coeur de contrecarrer point par point la propagande nazie.

En juin 1940, il suit le gouvernement jusqu'à Bordeaux.

A l'instar de nombreux journalistes, il se replie à Lyon après l'armistice. Au début de 1941, d'Astier, qu'il croise à Vichy, lui propose d'entrer à La dernière colonne. Copeau préfère partir en Tunisie pour rejoindre l'Angleterre. Revenu en France, il gagne l'Espagne, mais arrêté par la Guardia Civil, il est interné à Miranda.

En août 1941, remis aux autorités françaises, il est rapatrié en France et condamné à un mois de prison. Sa peine purgée, il rejoint l'équipe de Paris-Soir à Lyon.

A l'été 1942, par l'intermédiaire de Louis Martin-Chauffier, il fait la connaissance du résistant Emmanuel d'Astier, alors chef de Libération-Sud.

Copeau effectue une ascension fulgurante au sein du mouvement. D'abord responsable du journal clandestin, il assure l'intérim de d'Astier, parti pour Londres, dès l'automne 1942. A l'été 1943, il lui succède à la tête de Libération, qu'il représente au sein des Mouvements unis de Résistance (MUR), puis du Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR) dont il est membre du bureau permanent.

Dôté d'un calme imperturbable, d'une grande qualité d'écoute et capable des analyses politiques les plus fines, il parvient à s'imposer comme un modérateur et un conciliateur au sein des instances dirigeantes du CNR. " Je voudrais passer dans l’histoire de la Résistance comme étant l’un de ceux qui ont constamment poursuivi la notion d’unité », écrivait-il.

Dans le témoignage livré à la fin des années 1960 à son vieil ami Marcel Degliame, pour l'Histoire de la Résistance en France que ce dernier préparait avec Henri Noguères, Copeau se présente comme l'un des " chefs de la deuxième vague " par opposition à la génération des " chefs historiques " (d'Astier, Henri Frenay, Jean-Pierre Lévy). Il insiste sur le fait que les chefs historiques ont eu tendance à regarder ceux de la deuxième vague comme " des tard-venus ".

Certes, Copeau sait se montrer plus souple que d'Astier, tout comme Claude Bourdet manoeuvre plus en douceur que Frenay. Il reste que tous deux agissent, au sein des MUR, en défenseurs de leurs mouvements respectifs, et au sein du CNR comme les défenseurs des mouvements face aux partis politiques, y compris le parti communiste. Copeau excelle à promouvoir la ligne activiste des mouvements et parvient à trouver des points d'accord avec les diverses composantes du bureau du CNR, dont il est une figure de proue au printemps 1944.

A la Libération, on lui prédit un bel avenir politique. Tête de liste aux élections du 21 octobre 1945 avec le soutien du parti communiste en Haute-Saône, il est élu député. Il est réélu en juin 1946.

Il renoue par la suite avec ses activités de journaliste et part s'installer au Maroc. Fin 1964, il revient en France, où il obtient la direction régionale de l'ORTF puis de FR3.

La fin de sa vie ressemble à un long combat contre la dépression et la tentation du suicide. Pascal Copeau s'éteint le 8 novembre 1982, à Pouilly-en-Auxois (Côte-d'Or), victime d'une crise cardiaque au volant de sa voiture.

![]()

Pascal Copeau was born in Paris October 23, 1908. He was the son of a man of the theater Jacques Copeau who founded the Nouvelle Revue Française alongside of André Gide and Jean Schlumberger in 1908. In his childhood, he encountered artists and intellectuals alike such as Charles Dullin, Louis Jouvet, Gaston Gallimard and also Roger Martin du Gard.

A brilliant student, he undertook studies in history, law, and frequented l’Ecole Libre des Sciences Politiques. Knowledgeable in Danish, English, and German, he became a journalist and worked in Berlin from April 1933 until November 1936 as a correspondent for the Petit Journal. Upon returning to Paris in 1937, this anti-Nazi was convinced to become editor-in-chief of Lu and then of Vu et Lu where he gave orders to a journalist by the name of… Emmanuel d’Astier de la Vigerie.

In July 1938, thanks to Pierre Brossolette, Copeau was named responsible for the programs in German for Radio-Strasbourg before, in February 1939, being entrusted with the broadcasting of all foreign languages on the French radio. He was briefly mobilized in August and then recalled to the radio, where he counteracted point for point Nazi propaganda.

In June 1940, he followed the government to Bordeaux. Just as a number of other journalists, he went to Lyon after the armistice. At the beginning of 1941, d’Astier, who broke from Vichy, asked Copeau to become a member of La Dernière Colonne. However, he preferred to leave for Tunisia to join the British. Returning to France he made it to Spain but was arrested by the Guardia Civil and incarcerated at Miranda.

In August 1941, he was returned to French authorities and repatriated into France being condemned to a month in prison. After serving his time, he rejoined the team of Paris-Soir at Lyon. The summer of 1942, directed by Louis Martin-Chauffier, Copeau became connected to Emmanuel d’Astier, head of Libération-Sud.

Copeau made a lightning fast ascension within the movement. First responsible for the clandestine newspaper, he took over the duties of d’Astier, who left for London, in 1942. In the summer of 1943, he succeeded to the head of Libération and represented it within the United Movements of the Resistance (MUR) and then also in the National Council of the Resistance (CNR), of which he was a permanent member.

Equipped with an imperturbable calm and the ability to listen to and analyze politics carefully, he reached a position akin to a moderator during tense moments of debate in the CNR. “I would like to be remembered in the history the Resistance as one of those who constantly sought the notion of unity,” wrote Copeau.

In the written testimony of his oldest friend, Marcel Degliame, for L’Histoire de la Resistance en France that was prepared with Henri Noguères, Copeau is presented as one of the “heads of the second wave” as opposed to the generation of the “historical leaders” (d’Astier, Henri Frenay, Jean-Pierre Lévy). Degliame insists on the fact that the historical leaders had the tendency to view those of the second wave as “the late-comers”.

Of course, Copeau knew a suppler rise than d’Astier, much in the same fashion as Claude Bourdet maneuvered softer than Frenay. It remains that both acted, within MUR, in defense of their respective movements, and within CNR as defenders of movements facing other political parties, he representing the communist party.Copeau excelled at promoting the line of activism of the movements and proceeded to find common points between the diverse factions of the CNR, thus he is a figure more or less of the spring 1944.

At Liberation, people predicted him to have a bright political future. Ahead the list for the elections October 21, 1945 with the support of the communist party in Haute-Saône, he was elected deputy and then again reelected in June 1944.

He re-established afterwards his journalism activities and left to install himself in Morocco. At the end of 1964, he returned to France, where he obtained the regional direction of the ORTF and after FR3.

The end of his life was characterized by a long battle with depression and the temptation of suicide. Pascal Copeau died November 8, 1982 at Pouilly-en-Auxois (Côte-d’Or), suffering from cardiac arrest while at the wheel of his car.

Traduction : John Vanderkloot

D'après Laurent Douzou, "Pascal Copeau" in Dictionnaire historique de la Résistance, sous la direction de François Marcot, Robert Laffont, 2006 et Pierre Leenhardt, Pascal Copeau (1908-1982) L'histoire préfère les vainqueurs, préface de Lucie Aubrac, L'Harmattan, 1994.

Voir le bloc-notes

()

Voir le bloc-notes

()